The Union of Reserve Officers of the National Security Service of Armenia has issued a statement in which it "labeled" Leonid Kalashnikov, Chairman of the Russian State Duma Committee on CIS Affairs and Eurasian Integration, as pro-Turkish.

The Armenian Union of Reserve Officers of the National Security Service declares about Kalashnikov's position:

"After the appearance of Russians and Turks in the region, in the thirteen Russian-Turkish wars, the Armenians, having no statehood, were always on the side of the Russian soldier, they were his ally. Moreover, the appearance of Russia in the region was dictated solely by Russia's geopolitical interests, and not by the myth of the Armenians' salvation."

A few days earlier, Leonid Kalashnikov, in an interview with Svobodnaya Pressa, commented on the CSTO's refusal to come to "help" Armenia: "Delimitation is a subject of negotiations, not a war over two kilometers of the border. What is the point for Yerevan in attracting the CSTO - completely destroying the relations that have just begun to develop with Baku?! To resolve such issues by military force and even by involving Russia - is complete nonsense. The CSTO was not created for this!"

The well-known Russian journalist Mikhail Leontyev once stated that "the people of Armenia exist thanks to the support of Russia, and without Russia, there would be no Armenia."

To begin with, the Armenians do owe a great debt to Russia.

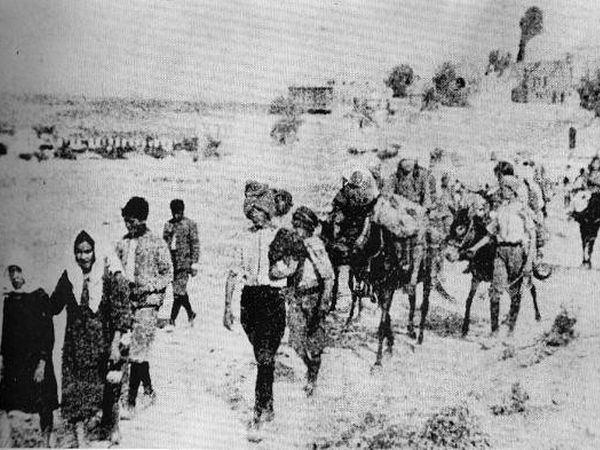

The mass resettlement of Armenians to the South Caucasus began due to the Russian-Persian and Russian-Ottoman wars of 1826-1829. As the Russian ethnographer N. Shavrov notes in his work, published in 1911 in St. Petersburg, "out of 1,300,000 Armenians living in Transcaucasia today, more than 1,000,000 do not belong to the indigenous population of the region and have been settled by us."

Indeed, during the period of regional wars, Armenians provided invaluable services to the Russian troops. This was especially noticeable during the two Russian-Persian (1804-1813, 1826-1828) and Russian-Turkish (1806-1812, 1828-1829) wars in the first third of the 19th century, in which the Armenians, who were fluent in Persian and Turkish languages, knowing the terrain, successfully collected information about the location and number of enemy troops for the Russian command, and often helped the Russian troops to break out of the encirclement, taking their troops across impassable and inaccessible roads.

Thanks to the information provided by the Armenian guides, couriers and spies, Russian troops very often unexpectedly appeared behind enemy lines and carried out successful attacks. It was a similar plot that formed the basis for the work of the Russian general and military historian Vasily Potto about the Armenian volunteers of Karabakh.

However, according to historians, the notion of "volunteer" does not correlate with the sincere desire of Armenians to help the Russian army. As can be seen in Potto's work on the Caucasian Wars, contrary to the assertion of modern Armenian authors, their compatriots tried in every way to evade this. It came to the point, as Potto writes, that the commander of the Russian troops in the Caucasus Pavel Tsitsianov had to appeal to the Armenians to fulfill the obligations promised to the Russian sovereign: "Have you, the Armenians of Karabakh, become effeminate and similar to other Armenians who are engaged only in trade. .. Come to your senses."

Then Potto notes that all the calls were in vain. And only by a happy coincidence, the son of an Armenian from Elisabethpol was next to Colonel Karyagin, to whom he once did a great favor. Therefore, he agreed to act as a guide and spy.

As a result, the Russian troops managed first to occupy the Shahbulag fortress, built in 1751 by the founder of the Karabakh khanate, Panah Ali Khan, and then, breaking out of the encirclement, unite with the main parts of the Russian army led by Tsitsianov. The Armenian spy was rewarded for his diligence, receiving the rank of ensign, a gold medal, and a lifelong pension of 200 rubles.

In a work devoted to the conquest of the Caucasus, the Russian historian P. Kovalevsky, describing in sugary tones the treacherous actions of local Armenians, which allowed the Russians to seize the most insurmountable fortress of the South Caucasus - the Irevan Khanate, noted:

"In 1827, the Armenians kept their word. Nerses, the Archbishop of Armenia, was one of the first to rush to the Russian regiments... When General Tuchkov entered Shirak, a hundred mounted Armenians immediately joined them. The Armenians were our loyal allies, intelligence officers, and assistants everywhere. Without separating their benefits from those of Russia, the Armenians informed Russians about the enemy's every movement, served as guides, and were on the field together with Russians."

Their new masters - Tsarist Russia, appreciated the collaborationism of the Armenians. In addition to the fact that the Armenians were rewarded with considerable money, orders, ranks, the former subjects of the Persian Shah and the Ottoman Sultan, whom they had betrayed, received the right to move to the lands of the South Caucasus, newly acquired by Russia. Here, at the expense of the local Muslim population, the settlers received vast lands, significant cash loans from the treasury and were exempted from duties.

However, it is known from history that, getting what they wanted, the Armenians began to create problems for their new patrons - the Russians. After the settlement of Armenians in the South Caucasus, most of them were concentrated on the territory of the former Azerbaijani Iravan Khanate, which became part of the Armenian region with the status of a province. In total, 3,674 Armenian families or 21,639 people were settled in the Iravan province. After the resettlement, the Armenians were granted privileges in paying taxes and duties, established under the imperially approved Regulations of October 22, 1819, which exempted migrants from paying state taxes for six years and from zemstvo duties for three years. When the grace period ended, the Armenian settlers refused to pay taxes on an equal basis with other province residents. Local authorities met with stiff resistance from Turkish Armenians, who refused to fulfill the obligations taken six years ago.

The chief governor of Georgia, Baron G. Rosen, mentioned this in his letter dated February 10, 1838, to the Minister of War A. Chernyshev concerning the report of the head of the Armenian region V. Bebutov. Moreover, the Armenians "even dare to offer the Muslims, who live in the Goycha mahal, to stick to them and not pay taxes."

On December 7, 1903, the head of the Askhabad convoy team, Lieutenant Colonel D.D. Kiselev reported to the Chief Inspector of the transfer of prisoners and the head of the stage-transfer unit of the General Staff:

"... Dislike of military affairs and anti-government propaganda has been widespread in this group of the population in recent years and serves as a clear indicator that Armenians cannot be a reliable military element, but are a factor that can adversely affect the discipline of their other comrades in service .... "

"... Secretly selling weapons to our enemies or taking them away during escape is a common thing for the lower ranks of the Armenians serving in the troops of the named corps, not to mention the fact that they are the most convenient factor for any foreign intelligence about our border troops, reserves, fortifications and current events ... "

As you can see, the Armenians have never been reliable allies of Russia but only used Russia's power to solve their own problems. This truth began to make itself felt by the end of the 19th century and early 20th century.

As follows from historical documents, during that period, the Armenians who settled in the empire's territory turned into a threat to Russian statehood.

On the eve of the First Russian Revolution, caches of weapons, ammunition, and illegal printing houses were found in many Armenian churches and parishes throughout the Caucasus. The tsarist autocracy realized that the so-called "spontaneous" disturbances in the Caucasus were controlled from abroad and carried out through Armenian organizations, mainly through the Dashnaktsutyun.

In October 1903, a member of the Gnchak party seriously wounded the tsar's governor in the Caucasus, Grigory Sergeevich Golitsyn. He was stabbed in the head by a dagger and died soon after. According to rumors circulating, the terrorists decided to behead the prince and expose his head on Yerevan Square in Tiflis. The fact is that back in 1897, Prince Golitsyn drew the tsar's attention to a dangerous tendency. It was about the fact that the Armenians seized all power in Tiflis and Baku.

"The Armenians think too much of themselves. Their church is helping to revolutionize the local population," Golitsyn wrote in his letter. After that, the prince imposed sequestration on the property of Armenian churches and issued a decree on the complete removal of Armenians from participation in city elections. The prince cared about the security of the Russian state and paid for it with his life.

Armenia's sham alliance makes itself felt in our time.

In 2015, the Armenian delegation abstained and did not vote against a resolution depriving Russia of the right to vote in the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE).

Making excuses, in an interview with Radio Liberty, the head of the parliamentary faction of the ruling Republican Party of Armenia (RPA) Vahram Baghdasaryan stated that in this way Yerevan "does not want to contribute to an even greater aggravation of relations between the West and Russia ... We must refrain from sharp orientations, because our status allows it," said Baghdasaryan.

The Russian delegation was deprived of the main powers - the right to vote and participate in some of the governing bodies of the Assembly. Reportedly, 160 delegates voted for the deprivation of the Russian delegation, 42 voted against, 11 abstained, including Armenia.

The Azerbaijani delegation voted against the resolution depriving Russia of the right to vote.

In 2019, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, by a majority vote of the national delegations of states, returned Russia to the Assembly and reaffirmed its full powers. Many drew attention to the fact that in the initial vote on the return of the Russian Federation to the Assembly, Russia's strategic ally Armenia did not vote unanimously. Moreover, a scandal erupted around the vote of the Armenian delegation.

So MP Hovhannes Igityan did not participate in the voting at all, and there are no explanations on this matter. Ruben Rubinyan, another representative of the ruling party and head of the Armenian delegation to PACE, voted against and then stated that it happened due to a technical error, and in fact, he voted for it.

There is a selective approach to the interests of the ally. When it is profitable for Armenia, it votes for these interests; when it does not see its own benefit, it votes against.

Thus, firstly, the Armenians do owe Russia a lot, first of all, statehood. Secondly, they have never been true allies of Russia but used its influence in their own interests, betraying Russia's interests at critical moments.